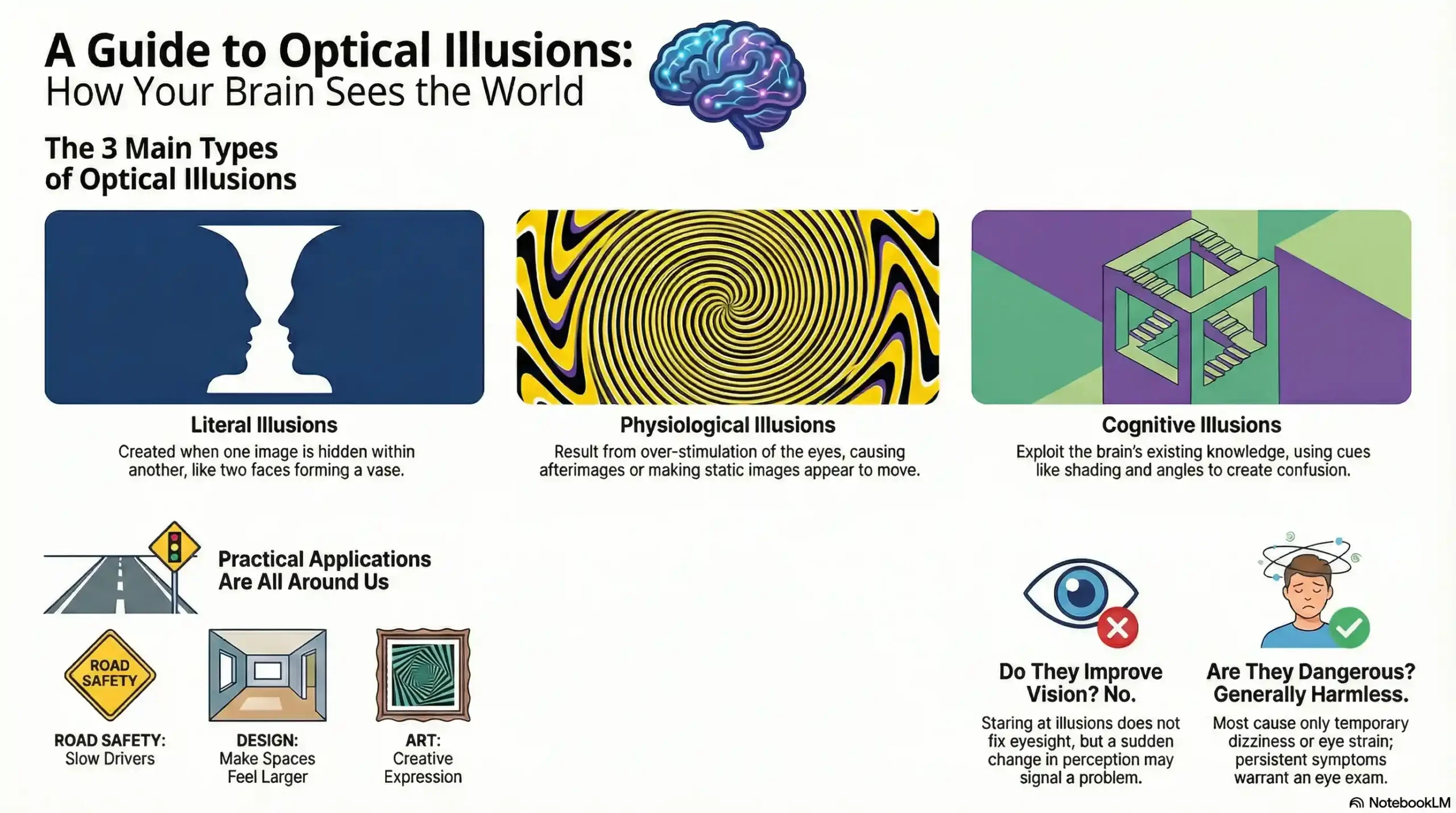

optical illusions and cognition are more closely linked than most people realize. When a flat image seems to move, shift in size, or hide shapes in plain sight, your brain is quietly revealing how it builds reality. In this article, we’ll use illusions as a window into attention, IQ-style reasoning, creativity, and even everyday decision‑making—and show practical ways to turn that moment of ‘Wait, what?’ into mental flexibility and fresh ideas.

When your eyes trick you, your brain’s algorithms are exposed

Picture this: you stare at two arrows in the Müller‑Lyer illusion. One line has arrowheads pointing outward, the other inward. You measure them and confirm they are exactly the same length. Yet every time you look, one still seems longer.

This isn’t a failure of eyesight. It’s your brain revealing the shortcuts it normally keeps hidden. Our perceptual system is not a camera that records reality; it is a prediction engine that constantly guesses what is out there and fills in gaps based on context, past experience, and goals.

Researchers who study optical illusions and cognition often explain perception using the idea of top‑down processing: your expectations and prior knowledge flow down and shape the raw flicker of light on your retina. In the Müller‑Lyer illusion, your brain interprets the arrows as depth cues, as if one line recedes into the distance and one comes toward you, so it “corrects” the image in a way that normally helps—but here it backfires.

In a lab, this becomes a superpower for scientists: illusions act like X‑rays for mental processes. By tweaking contrast, color, or orientation and watching where perception breaks, they can infer how attention, working memory, and pattern recognition operate behind the scenes.

A designer’s moment of insight: a short story from the studio

Lena, a graphic designer preparing a portfolio for a competitive creative agency, was stuck. Her layouts felt flat, and her concept sketches all looked the same. Late one night she scrolled past a classic checker‑shadow illusion: a gray square on a “shadowed” part of a chessboard looks much lighter than an identical square in the “light,” even though a color picker shows they’re the same shade.

She dropped the image into her editor, pulled up the color values, and felt that strange mixture of disbelief and delight. If she could be so sure two shades were different when they weren’t, what else in her designs was being subtly shaped by unconscious assumptions?

Lena started playing. She overlaid geometric shapes, inverted figure and ground, and asked herself, “What if the background is actually the main character?” Within a week, her posters changed dramatically. By leaning into illusions—ambiguous figures, impossible shapes, playful shadows—she not only refreshed her visual style but also trained herself to question first impressions in client briefs and brand guidelines.

Her mini‑revolution points to a broader truth: illusions are not just party tricks; they are tools for metacognition, the ability to think about your own thinking. Once you see your perception glitch, you become more curious—and that curiosity is rocket fuel for both creativity and problem‑solving.

What illusions teach us about IQ, reasoning, and test performance

Standard intelligence tests and visual illusions might seem worlds apart, but they both rely heavily on how we detect patterns and ignore distractions. In IQ testing, scores are often normed so that the average is set at 100 with a standard deviation of 15. That scaling doesn’t mean 100 is “perfect”—it just tells you where a score falls compared with a large, carefully sampled population.

One of the best known measures of abstract visual reasoning is Raven’s Progressive Matrices. In this test, you see a grid of patterns with one piece missing and must choose the option that logically completes the sequence. Although Raven’s items are not illusions in the classic sense, they exploit the same kinds of mental processes: spotting what changes and what stays constant, resisting misleading cues, and mentally transforming shapes without getting lost in the details.

Illusions make it clear that perception is malleable, and that has implications for test performance. Psychometric research shows that so‑called practice effects exist: if you become familiar with the format of puzzles or matrix items, your scores can improve slightly over time, even though your underlying reasoning ability has not dramatically changed overnight. The brain becomes more efficient at ignoring irrelevant features and zooming in on the structural pattern—skills also trained when you repeatedly analyze why an illusion works.

So while illusions won’t magically add 30 points to an IQ score, working with them can sharpen the same visual‑analytic habits that help in aptitude tests, spatial reasoning challenges, and problem‑solving tasks used in talent selection or gifted education.

Attention, distraction, and why illusions fascinate ADHD researchers

Many people with ADHD describe visual scenes as noisy: details compete for attention, and it can be harder to filter what matters most. Illusions offer a controlled way to study how attention jumps around a visual field and what grabs it most strongly.

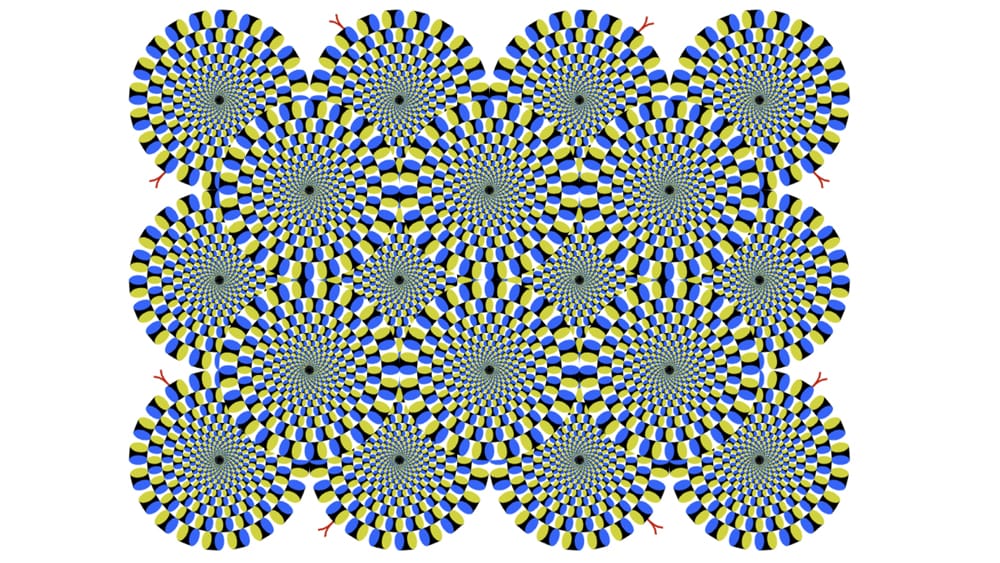

Consider a motion illusion where a static image seems to shimmer or rotate. Your eyes dart across the pattern, and the “movement” strengthens. Experiments using these kinds of stimuli can reveal how quickly someone’s attention shifts, how easily they can hold focus in one area, and how well they can suppress the urge to chase every flicker. None of this is diagnostic on its own, but it deepens our understanding of attentional control and variability across people.

For anyone—ADHD or not—illusions are a reminder that focus is partly a decision and partly an automatic response. You can choose to stare at the “wrong” answer in an illusion and feel how hard it is to override. That experience builds empathy for anyone who struggles with distraction and gives you a more realistic appreciation of how limited and biased attention can be.

Illusions as a creativity gym for the brain

Creativity tests, such as alternative uses tasks or drawing challenges, often measure how flexibly you can reinterpret a simple object. Optical tricks train a similar skill: reframing.

Ambiguous images—like the classic duck‑rabbit or the vase that flips into two faces—demand mental set‑shifting. At first you see one interpretation. Then, with a nudge, the image flips. Each flip is a tiny creative act, proving your brain can abandon a stable interpretation and build a new one from the same raw data.

You can turn this into a structured creativity workout:

- Describe three realities: For any illusion, write three different explanations of what might be happening in the picture, as if each were true. This forces you to practice flexible narrative building—useful for storytellers, UX designers, and even lawyers.

- Borrow the principle: If an illusion uses hidden contours (like the Kanizsa triangle, where you “see” edges that are not drawn), ask how you could use implied information in your work. In English writing, that might mean hinting at a character’s motive without stating it; in product design, it might mean guiding user behavior through subtle visual cues rather than explicit labels.

- Reverse the trick: Try to create your own mini‑illusion that makes people misjudge size, brightness, or depth. The process of building the trick deepens your understanding of visual rules and pushes you to think like a scientist and artist at the same time.

Over time, these exercises train the habit of asking, “What else could this be?”—a core question in divergent thinking and creative problem‑solving, whether you’re brainstorming ad campaigns or reimagining a study schedule for an entrance exam.

Practical ways to weave illusions into learning and work

If you teach, coach, or simply want to sharpen your own thinking, illusions can be turned into simple, low‑prep tools that make cognitive concepts tangible.

1. Kick‑off prompts for IQ, aptitude, or MBTI workshops

Before diving into test prep for an IQ or aptitude assessment, or discussing personality frameworks like the MBTI, show a visual illusion and ask participants to silently write their first impression. Then reveal the trick and discuss how expectations shaped perception.

This sets the stage for a nuanced conversation: scores and personality types reflect how we process information under specific conditions, not fixed labels of worth. It primes people to see assessments as maps of tendencies rather than rigid boxes.

2. Attention drills for focused study sessions

Use illusions to practice selective attention before a deep‑work block:

- Pick a complex illusion with many elements.

- Set a timer for 60 seconds and focus only on one region or shape, ignoring the rest.

- Notice every urge to look away, but gently return to the target region.

This brief drill mirrors the skill you need when revising English passages for an exam or working through multi‑step logic problems: holding your focus on the relevant clause, sentence, or symbol despite background noise.

3. Creativity warm‑ups for writing and design

In a writing class or creative workshop, display an illusion and ask participants to write a short scene from two different viewpoints: first from the perspective that sees one interpretation, then from the perspective that sees the other. For example, with the duck‑rabbit image, one narrator insists they’re staring at a duck, the other at a rabbit. This naturally cultivates perspective‑taking and narrative flexibility.

Design teams can do something similar by sketching how a user with high need for clarity versus a user who enjoys ambiguity might react to the same visual layout modeled on an illusion.

4. Exploring online illusion tests thoughtfully

Many websites now offer illusion‑based quizzes and mini cognitive tests that claim to reveal your attention style or creative type. These can be fun starting points—as long as you treat the results as conversation pieces, not diagnoses. If you are curious, pick a reputable research‑oriented site, explore a few illusions, and when you are invited to compare your performance to others, pause and reflect on what the patterns suggest rather than fixating on any single score. Start the test now, but use it as a mirror for curiosity, not a verdict on intelligence.

Drawing back the curtain on perception

Every optical trick that makes you doubt your own eyes is really an invitation to observe your mind in action. Illusions reveal that what feels immediate and obvious—the “size” of an object, the “motion” of a pattern, the “truth” of a first impression—is actually the result of complex, mostly unconscious computation.

For people interested in IQ, ADHD, MBTI, language learning, or creativity, this is liberating news. It means that your cognitive style, strengths, and struggles are partly shaped by how your brain predicts and edits the world—not by a single number or label. You can’t stop illusions from working on you, but you can learn from them: notice how context sways judgment, how practice refines pattern detection, and how deliberately flipping perspectives becomes easier with time.

Using optical illusions and cognition‑focused exercises will not turn you into a superhero overnight, but they can help you become a more reflective thinker, a more flexible problem‑solver, and a more imaginative creator. Each time an image fools you, ask not “Why is my perception wrong?” but “What is my brain trying to do for me—and how can I use that knowledge in my next challenge?”

Common questions about illusions and thinking

Do optical illusions mean my brain is ‘wrong’?

No. Illusions highlight that your perception system is optimized for everyday survival, not for perfect measurements in artificial situations. The same shortcuts that cause you to misjudge line lengths or brightness usually help you recognize objects quickly, read faces, and navigate cluttered spaces. When an illusion “wins,” it is less a sign of defect and more a reminder that context and expectation are always part of what you see.

Can practicing with visual puzzles improve my IQ score?

Practicing with puzzles, including illusion‑like pattern tasks, can produce small gains on some tests, mostly through familiarity with item types and strategies. This is related to practice effects: as you learn what to ignore and what to focus on, you work more efficiently. However, such improvements tend to be modest. The most valuable benefit is usually not a higher number, but better problem‑solving habits you can transfer to studies, work, and creative projects.

How can I use optical illusions to boost creativity in a classroom or workshop?

You can integrate illusions as brief, high‑impact prompts. Start a lesson by displaying an illusion and asking students to brainstorm alternative explanations; use ambiguous images to practice perspective‑taking in storytelling; or challenge groups to invent their own illusions based on concepts being studied (for example, using grammatical ambiguity in an English class). This keeps sessions lively while quietly training flexibility, curiosity, and critical thinking.

Related resources

optical illusions and cognition: improve your results by practicing and tracking progress.